When I was a new PI I knew what I valued in a research group – a fun, collaborative, inclusive lab culture that values everyone’s opinion and with a variety of backgrounds and perspectives. I also felt that change towards a more diverse and inclusive research culture – within my organisation and academia in general – was happening too slowly. Toxic workplaces are an important reason why people leave academia, and toxic leadership, bullying, and harassment can often continue for years before disciplinary action is taken. Yet, no best practices are present for PIs on how to manage and structure their research groups, essentially leaving the environment in which we train and foster the next generation of scientists to the actions or inactions of individual researchers, with all the associated risks. See for example this and this harrowing recent example from the Netherlands.

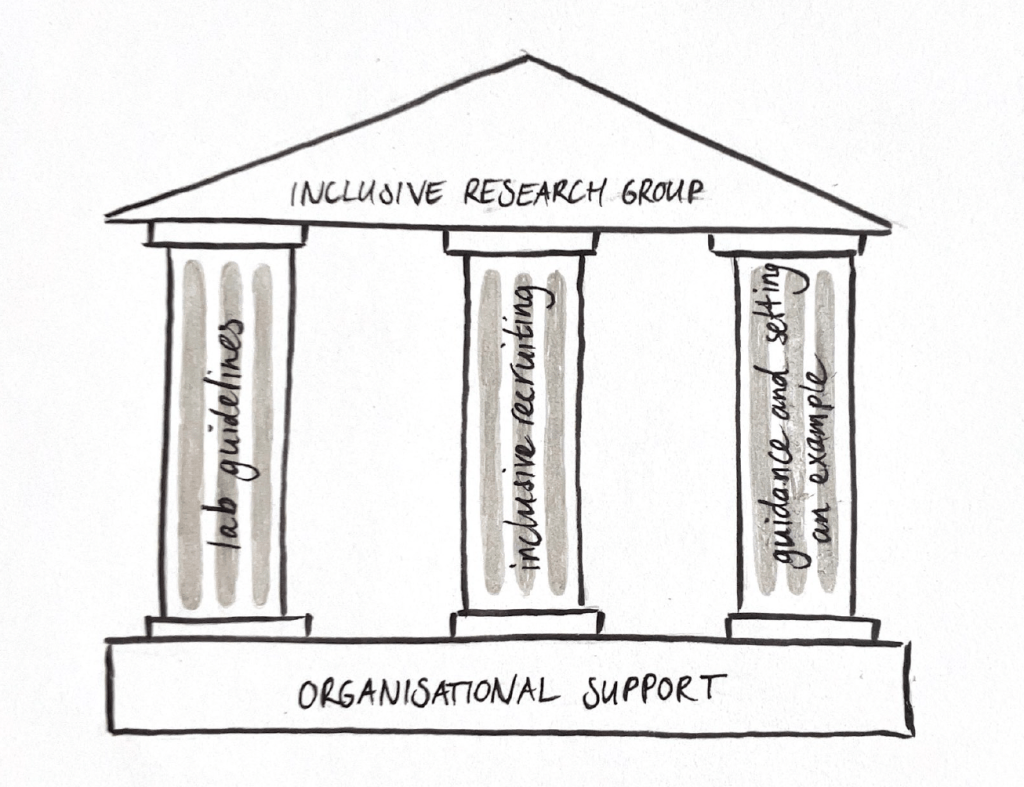

Frustrated by all this, I decided to change the things I can control, from the bottom up, and to hopefully in the process inspire others. Although things are never perfect, I genuinely feel that I have succeeded in building an inclusive, diverse, and supportive lab. Here are the three main pillars that I believe are key to accomplishing this.

Co-creating lab guidelines and frequently revisiting these

There is a lot of information out there of the basic ingredients of a diverse and happy lab. Essential reading are the “Ten simple rules towards healthier research labs” and the “Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab”, but also lab guidelines created by other labs, such as those of the Duffy lab. However, for a set of guidelines to be supported by everyone in our lab, I felt it was necessary to jointly create and agree on these with all lab members – this ensures that everyone agrees on these, and it’s also a great starting point for discussions on what constitutes an inclusive lab. Once these guidelines have been established, it is essential to revisit and revise them frequently to make sure that everyone is aware of these – this is particularly important when new lab members are starting. But also, spread the word about these guidelines! Post them on your website (see ours here!) and talk about them to colleagues. It might inspire others and draw people to your group – having these lab guidelines upfront helps potential applicants find out about your lab culture.

Inclusive recruiting

Inclusive recruiting is not just about gender, ethnicity, or background. It’s also about skills, experience, perspectives, and personalities that can strengthen the group and the research that is being done. Whenever I am advertising for a new postdoc or PhD position, I ask the group for input, and I write the advert with this in mind. I also make sure the advert uses inclusive language, does not use overly masculine words, and emphasises the collaborative nature of the research group, as well as links with information on the organisation (and, of course the lab guidelines). This shows that you are serious about inclusivity and works better than simple oneliners about valuing diversity. There is a lot of information on inclusive recruiting available, see for example this great infographic, and I’ve also taken part in an inclusive recruiting trial through my institute.

I also include contributing to the inclusive nature of the research group explicitly as a requirement in the advert. This again makes it clear that you are taking concrete actions towards inclusivity, and that team members are expected to contribute to these. The advert should be published far and wide, if possible on job boards for underrepresented groups, and certainly not just within your own network. Shortlisting should happen based on clear criteria and transparent ranking, by a panel that is as diverse as possible and is aware of their own biases.

Inclusive recruiting doesn’t stop when the shortlisting is done, though I haven’t found any resources on inclusive interviewing in academia. You can interview more inclusively, ease applicants’ nerves, and save them the embarrassment of having to ask for special facilities or reimbursement of expenses. In the interview invitation, I include expenses reimbursement forms upfront, ask if they need any facilities or assistance to attend the interview, disclose the names of the panel members, and provide them with a clear outline of what the interview will consist of, including timings and directions. I also indicate the types of questions they can expect, and I send a few questions in advance of the interview that they can prepare for. I also like to include a question on how they see a research group functioning and what their role is in that. This all indicates that you take your applicants seriously, helps to take away (some) anxiety, and reduces the chances of recruiting for only one trait: smooth talking.

Guidance and setting an example

I am not perfect. I make mistakes and I am learning every day. I recognise that as a PI, I am responsible for the above two pillars, for the supervision of my team, and for guidance and setting an example. That includes collaborating with and promoting the visibility of scholars from underrepresented backgrounds or countries, being vocal about diversity and inclusivity to the outside world, and stimulating collaboration and network opportunities for my group members. It involves supporting in the next steps in their career, speaking up for them and fighting for their rights, as well as calling out unacceptable behaviour and moderating conflicts within the research group.

For a PI to be able to do all this, they need time, support, and resources. Implementing and managing all this needs to happen on top of an ever-increasing workload. Dealing with struggling team members or internal conflicts can be stressful and take its toll on the PIs wellbeing, often in the absence of support or care for the PI themselves. But if we share experiences and best practices, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel, and if organisations have a better awareness of the benefits of inclusive research groups, there may be more support and recognition. Of course, basic organisational structures, such as facilities for disabled people, lactation rooms, career services, training opportunities, and a social safety plan and support, as well as clear procedures for when things go wrong, are crucial for enabling the long-term success of diverse and inclusive research groups.

Being part of a diverse and inclusive lab makes me proud and brings me joy every day. Training the next generation of scientists and professionals is arguably the biggest impact we have as academics, and it is on us to do this in a safe, supportive, and inclusive environment. This does not go at the expense of impactful science – happy people that feel supported are the most productive! Academia would be a better place if more PIs would build, and more organisations would support and foster, inclusive research groups.

Leave a comment